The Bank in Your Wallet

Think airlines run the points game? Cute. The banks own the house, mint the chips, and set the odds. Every swipe funds the show: cheap miles bought in bulk, annual fees as cover charge, and interest as the trapdoor. Your “free” trip? A payout planned on their spreadsheet.

If You Only Had 60 Seconds to Read This Article (Click Here 🗞️)

Banks (not airlines or hotels) run the loyalty casino. They buy points in bulk for pennies, then dangle huge sign-up bonuses as cheap customer acquisition. Annual fees are guaranteed cover charges, and perks are engineered to create just enough FOMO to keep you renewing. Points are a private currency the banks mint, price, and steer with transfer ratios, promos, and category multipliers.

Every swipe pays a toll called interchange, and premium cards collect a bigger toll. In the $100-at-Trader-Joe’s example, the bank might skim about $1.80, “pay” you 2 points that cost it roughly a fraction of that, and pocket the spread - before even counting your annual fee. Co-brand deals funnel loyalists into tight loops, while transfer partnerships let banks nudge redemptions toward their cheapest liabilities. Breakage and mediocre redemptions are pure margin.

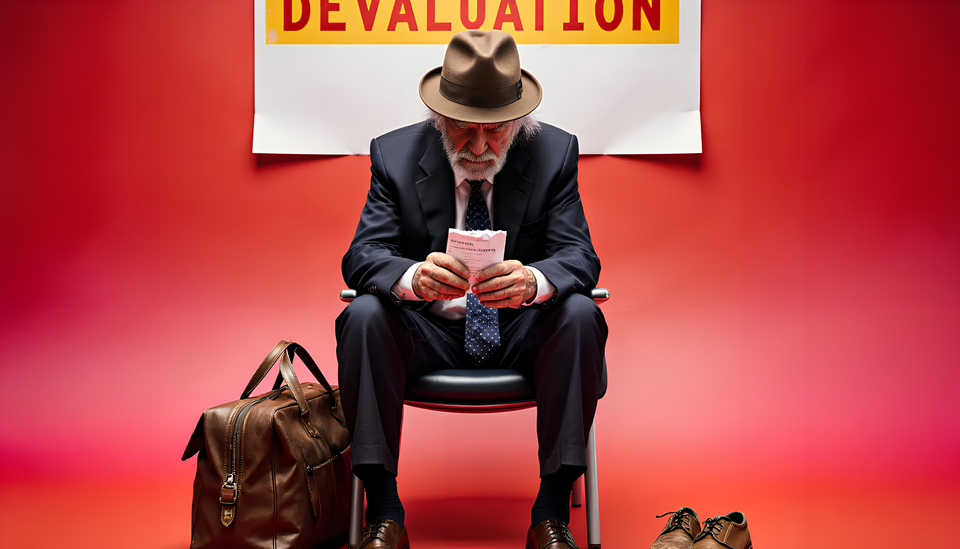

Rewards aren’t “free” - the dark side is interest and late fees from revolvers, which subsidize the fireworks for transactors who pay in full. Devaluations are inflation for private scrip: partners move goalposts, your dream trip drifts farther away, and you respond by swiping more to “catch up.” Bigger bonuses keep coming because the spreadsheets say lifetime value more than covers the headline bribe.

Play only if you can be cold-blooded. Pay in full, value points conservatively, be disloyal to brands, and downgrade ruthlessly when the math breaks. Redeem for trips you’ll actually take, not a someday that keeps moving. The punchline doesn’t change: the house owns the building; you’re just renting the view.

Everything else you need to know is just below 👇🏻

🎞️: Powered by NotebookLM @ UpNonStop

Walk into the loyalty casino and the first thing you see are the flashing lights - first-class suites, honeymoon overwater villas, “free” vacations paid for with points. The floor is crowded with games (airlines, hotels, and point programs), each promising life-changing jackpots. But the cage, the vault, and the dealer all answer to the same house. The banks run it. The brands you recognize - your preferred airline, the hotel you swear “treats you like family” - are just themed tables. The real business isn’t flying you to Paris; it’s moving money, harvesting fees, and selling hope at scale. Once you see who sits in the pit boss chair, the magic trick isn’t so mysterious: your card is a bank product; the points are a bank-controlled currency; and the trip you booked was just a line item on a spreadsheet where someone, somewhere, captured their spread.

How the casino actually makes money

The basic loop is simple. Banks issue credit cards. You spend. Merchants pay a toll called interchange every time your card runs. Networks take their cut for routing the transactions. Co-brand partners sell points to banks at wholesale prices. The bank then turns around and “rewards” you with those cheap points, funded by the toll on the merchant, the annual fee you paid for the privilege of being loyal, and the interest and late fees paid by the people who didn’t read the part about “Pay Statement Balance.” The loop is greased by marketing so shiny you can see your reflection in it. The house takes no real directional risk because it controls the rules, the payouts, and the pace of the game.

The bulk points racket: buying miles for pennies, selling dreams for dollars

Why do banks fund huge sign-up bonuses? Because they’re buying points the way Costco buys pallets of paper towels - wholesale. The bank commits to enormous tranches of miles from airlines and hotel chains at a negotiated price. Those points sit on the bank’s books like inventory. When a marketing team wants to juice new accounts, the bank pushes some inventory out the door: 80K here, 100K there, maybe 150K if the quarter needs a little sparkle. To you, the points feel like a gift. To the bank, they’re a calculated acquisition expense with a predictable breakage rate and redemption cost. And because the bank can steer redemption by leaning on transfer fees, category bonuses, and aspirational advertising, it can make sure the average penny paid out is comfortably lower than the pennies collected.

Sign-up bonuses as customer acquisition math, not charity

A six-figure bonus looks extravagant from the outside. Inside the machine, it’s line-item math. A cardholder who keeps the card beyond month twelve, runs a few thousand dollars a month, occasionally dips into a 0% promo, and maybe pays an annual fee is a profit center measured over years. The bank knows how many new accounts will never hit the minimum spend, how many will downgrade, how many will stick for five years, and how many will mess up once and pay interest. The expected value of a cohort - spread across interchange, fees, and a blend of redemption costs - easily justifies a headline number that makes social media gasp. Dark comedy translation: “Chase doesn’t lose money on your 100K bonus - they bought those miles for less than your Netflix subscription.”

Annual fees: the guaranteed-cover charge

People argue about whether a $95 or $695 annual fee is “worth it.” The bank doesn’t argue; it applauds. Annual fees are guaranteed revenue that lands even if you barely use the card. Credits, lounges, and “free” nights are structured to look generous while nudging you toward break-even behaviors that keep you paying. Some credits demand activation hoops. Others steer you to merchant partners the bank monetizes elsewhere. That “anniversary night” is capacity-controlled and often redeemed on off-peak dates that keep the partner hotel’s incremental cost low. The fee is an annuity; the perks are guardrails. The house wants you to feel friction when you think about downgrading and to feel FOMO when renewal season arrives.

Breakage, inertia, and the profitable power of almost

If there is a secret sauce in loyalty economics, it’s “almost.” Almost enough points for that business-class seat. Almost enough credits used to justify the fee. Almost enough spend to hit the next threshold. Points that never get redeemed are pure margin. Points redeemed for poor value are nearly as good. Banks engineer apps, dashboards, and transfer partner menus to keep you feeling close to something great - close enough to keep swiping, not quite close enough to cash out and quit. The average cardholder is a gold mine of inertia: too busy to optimize, too optimistic to cancel, and too allergic to math to notice the slow bleed.

Interest and late fees: the dark side that subsidizes rewards

The gentlest lie in credit card marketing is that “points are free.” They are free like casinos are free when you win your first hand. Somewhere else on the P&L, a different cohort is paying dearly. Revolvers - people who carry balances - fund a disproportionate share of the fireworks. Interest rates on rewards cards skew higher because the benefits have to be financed, and the moment a cardholder slips, compounding does its merciless work. Late fees are the sting that reminds you the house is not sentimental. In aggregate, these dollars subsidize the aspirational economy for transactors - the folks who pay in full every month. It’s a neat trick: the house can be Santa Claus to the disciplined while playing landlord to the forgetful.

Interchange: the silent tollbooth on every swipe

Interchange is the toll paid by the merchant’s acquiring bank to the issuing bank when you use your card. You never see it, but you feel it in the prices you pay. Premium rewards cards generally carry higher interchange, which is why some small shops frown when you flash a metal slab. The bank loves that higher rate; it funds a buffet of points, lounges, and influencers. Networks skim assessments off the top for running the rails. Processors and gateways take their thin slices, too. Your $100 grocery run is a conga line of micro-rents. The beauty of interchange, from the bank’s perspective, is that it scales with your lifestyle. The richer the card tier and the more you spend, the bigger the toll - no persuading required.

Co-brand agreements: whose brand, whose money?

Co-brand deals - the cards with an airline’s tail or a hotel’s logo - are marriages of convenience. The bank gets a captive audience of brand loyalists and the exclusive right to issue a card that “earns faster.” The airline or hotel gets a waterfall of cash for selling points to the bank and a lock on your future bookings when you chase status. The economics are meticulously negotiated: how many points per dollar on various categories, how much the bank pays per point, whether the brand kicks in elite status shortcuts, and what marketing obligations each side has. From your point of view, it’s a shiny piece of plastic that makes you feel known. From theirs, it’s an instrument that channels your spend into the tightest possible loop.

Transfer partnerships: the bank’s central bank trick

Banks run their own flexible points currencies and maintain webs of transfer partners. This is the central bank trick: the bank mints a currency (points), sets an exchange rate (transfer ratios), and then manipulates demand by adjusting category multipliers, limited-time bonuses, and redemption interfaces. Transfer bonuses to specific partners stimulate the exact breakage and cost management the bank wants this quarter. Keep enough levers in motion and you can nudge redemptions away from high-cost partners and toward cheap ones, all while your customers gush about “amazing value” they uncovered with a blog post and two late-night clicks.

The $100 Trader Joe’s run: who pockets what?

Let’s walk through the hypothetical. You pay $100 at Trader Joe’s with a bank-issued card. Interchange on that transaction might be around $1.80 on a premium product. Out of that, the bank owes you “rewards.” Suppose your card earns 2 points per dollar on groceries. The cost to the bank to grant you those points is nowhere near the “2% back” headline - because the bank buys points in bulk at a discount or uses its own currency at a fraction of face value. Let’s say the bank’s internal cost is roughly 1.2 cents per point. Your 200 points cost the bank $2.40 in liability, but now zoom out. The bank also collects the $95 annual fee from thousands of cardholders, spreads its marketing and servicing costs across the portfolio, and makes additional money from interchange on all your other spending categories where its costs are even lower. That $1.80 isn’t “the bank’s only revenue on the swipe.” It’s part of a mosaic in which the bank keeps the spread most of the time, especially when you redeem sub-optimally or keep chasing a premium card for benefits you barely use. And if any part of your financial life slips into interest territory, the margin on that $100 grocery run fades into background music.

Why bonuses keep getting bigger

The answer isn’t generosity; it’s competition plus data. Banks can model lifetime value down to the month. They know how many of you will product-change, how many will add authorized users, and how many will channel rent, taxes, and insurance through the card via payment services that carry extra fees you pretend not to notice. When a rival launches a headline-grabbing offer, the bank doesn’t panic - it recalibrates. Bigger bonuses are rational if they retain premium spenders, keep you from churning to a competitor, and feed a flywheel of interchange that the annual fee and breakage easily support. It’s Vegas with better spreadsheets.

Devaluation: the partner’s favorite lever, the bank’s favorite scapegoat

Every points hobbyist fears the late-night email: “We’re updating our award charts.” Translation: your dream trip just moved three squares farther away. Airlines and hotels devalue because they can; their liabilities are denominated in points, not dollars, and accounting pressure loves a devaluation. Banks pretend to frown, but devaluations often help the portfolio’s economics. Your hoard looks less spendable, which nudges you to earn more points to “catch up,” which means more swipe, more interchange, more annual fees renewed. If you think of devaluations as inflation in a private currency, you’ll see how neatly the system protects the house.

Who actually wins? (Besides the house.)

Transactors - people who pay in full - win when they extract outsized value from redemptions, use benefits they’d otherwise pay for, and avoid lifestyle creep. Gamers win occasionally if they treat points like business inventory and remain cold-blooded about canceling and moving on. Small merchants rarely win; they absorb the toll and pass it along in prices, which means cash customers end up subsidizing premium cards. Revolvers - the folks paying double-digit APRs - lose the moment they stop paying in full. The house wins by keeping all of them at the table, each convinced the next hand is theirs.

How to play without becoming the product

If you insist on playing, treat the card like a payment instrument, not a piggy bank. Pay in full, always. Ignore coupons disguised as perks. Value points conservatively and be disloyal by design - loyal to your own math, not a brand’s story about you. Keep only the cards whose benefits you harvest in cash terms every year. Downgrade ruthlessly when the math stops making sense. Redeem for trips you’ll actually take rather than hoarding for a someday that keeps moving. The house wants you dazzled; the counter is quiet, and the calculator fits in your pocket.

The theater of status and why banks bankroll it

Status is theater: early boarding, a free drink, a carpet of a different color. Banks bankroll the stagecraft because it keeps you earning the brand’s currency - and therefore using the bank’s card. Fast tracks, “spend X for Y status,” and companion certificates that require paid fares are all mechanisms to keep your spend local. Once status enters the chat, rationality leaves. You’ll route business through a card to protect a tier you barely exploited last year, and the bank will applaud from the balcony as your interchange fattens their margins.

The future: more rails, more rent, more you

Expect more categories to be pulled into the card universe. Transit, utilities, taxes, tuition, rent - anything that can be pushed over card rails will be, often with “convenience fees” that look small next to the points you imagine you’ll earn. Expect “buy now, pay later” to get woven into card portfolios to catch customers at more price points. Expect more slick mobile wallets and tokenized transactions that feel safer while preserving the tollbooth. Regulation might shift the price of interchange or late fees, but the house is nimble. If one hallway narrows, another opens.

The punchline: the house never loses

You can “beat” the casino by playing only when the odds tilt your way, but you can’t beat the fact that the casino owns the building. Banks run the loyalty economy because they own the rails, price the currency, buy the inventory, and design the stage. Airlines and hotels are storytellers paid in bulk sales and brand equity for keeping you entertained. The card in your wallet is the pit pass; the fee is the cover charge. Swipe if you want. Earn if you can. Redeem with intent. But don’t confuse champagne in a lounge with profit. The banks are the puppet masters because they wrote the script and cast the audience. The rest of us are extras with decent seats - so long as we remember to leave when the credits roll.